Click for pdf: Approach to Thrombocytopenia

DEFINITION

Thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count of less than 150 x 109/L.

REVIEW OF PHYSIOLOGY

Platelets are fragments of the large megakaryocyte, produced in the bone marrow. Under the influence of thrombopoietin, a chemical made by the liver and kidneys, the hematopoietic stem cell differentiates into the megakaryoblast. The megakaryoblast matures into the megakaryocyte, which has a nucleus with many lobes and a large cytoplasmic volume. Platelets are made when fragments of this cytoplasm pinch off the large cell. Each megakaryocyte makes about 4000 platelets. The platelets then enter circulation and have a lifespan of 7-10 days. They are cleared from the body by the spleen, and to a lesser extent, the liver and bone marrow.

Platelets have the important function of primary hemostasis. Hemostasis is the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel. They respond to damage of small vessel walls by plugging the site of injury and preventing blood leakage. Their membranes are covered with glycoproteins and receptors that respond to environmental signals, produced during endothelial damage, to adhere (platelets stick to the vessel wall) and aggregate (platelets stick to each other).

CLINIAL PRESENTATION

The manifestations of thrombocytopenia are due to the defect in primary hemostasis.

- Petechiae

- Bruises or purpura

- Bleeding of mucous membranes: epistaxis, gingival bleeding

- Acute gastrointestinal bleeding

- Menorrhagia

- Hematuria

- Acute CNS hemorrhage: the rarest but MOST FEARED consequence of low platelets

The body has a high reserve of platelets. Platelets actually have to be quite low before there are clinically evident consequences, with primary hemostasis effective until platelets fall below 75×109/L. The following is what you may expect to see given a patient’s platelet count:

| Platelet count(x109/L) | Risk of bleeding | Examples |

| <75 | Primary hemostasis impaired | After major surgery, trauma |

| <50 | Spontaneous bleeding, mostly seen in skin | Petechiae, purpura |

| <20 | Noticeable hemorrhage, seen in skin and mucosa | Epistaxis, gingival bleed |

| <10 | Possible life-threatening hemorrhage, mucosa and CNS | Acute GI hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage |

Deep tissue bleeding, including in internal organs, muscle, joints or not commonly associated with thrombocytopenia. These manifestations are seen in defects of secondary hemostasis, i.e. coagulation disorders.

Differential Diagnosis: A Pathophysiologic Approach

What can cause low platelets?

Decreased platelet production

- Pancytopenia

- Primary malignancy e.g. leukemia

- Bone marrow infiltration e.g. neuroblastoma

- Bone marrow failure e.g aplastic anemia

- Viral infections e.g. HIV

- Cytotoxic drugs, radiation

- Selective ineffective thrombopoiesis

- Rare congenital defects e.g thrombocytopenia-absent radius (TAR) syndrome, Wiskott Aldrich syndrome, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia and giant platelet disorders (e.g Bernard-Soulier syndrome)

- Viral infections e.g EBV, CMV, parvovirus

Increased platelet consumption

- Immune

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) (most common cause of thrombocytopenia in children)

- Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT)

- Collagen-vascular and autoimmune diseases, e.g. SLE

- Viruses e.g. HIV

- Drug-induced e.g. heparin

- Nonimmune

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS)

- Sepsis

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

Platelet sequestration

- Hypersplenism

- Infection

- Inflammation

- Congestion

- Red cell disorders

- Storage diseases

Dilutional loss

- Recent massive blood transfusion

| Questions to ask | Why should you ask? |

General health/constitutional symptoms:

|

Malignancy, infection |

Sources of bleeding:

|

Estimate amount of blood loss |

| Previous/current URTI | ITP, immune-mediated |

| Diarrhea (bloody), oliguria, edema | HUS |

| Infections contacts, travel history | HUS, ITP |

| Chronic liver or storage disease | Cause of splenomegaly |

| Recent massive transfusion | Dilutes patient’s own platelets |

| Recent vaccine | Small risk of ITP after live vaccine (e.g. MMR) |

| Medications | Adverse drug reaction |

| Family history | Hereditary thrombocytopenia (e.g. ineffective thrombopoiesis, short life span), familial TTP |

| Inquire about complicationsAmount of active bleedingHeadache, focal neuro symptoms, weakness |

| Physical Findings | What would this suggest? |

| General appearance: unwell/toxic | Infection, malignancy, DIC, TTP |

Vitals

|

Infection, malignancy, DIC, TTPHUSBlood loss |

Sources of bleeding

|

Low platelets, risk of anemia |

| Lymphadenopathy | Malignancy |

| Splenomegaly | Splenic sequestration of platelets |

| Renal failure e.g. edema, HTN | HUS |

| Abnormal neuro exam eg. hemiparesis | Intracranial bleed, TTP |

| Investigations | What are you looking for? |

| CBC | Pancytopenia vs. isolated thrombocytopenia |

| RBC indices, reticulocytes | Mild anemia may be due to bleeding, but look for other causes of anemia |

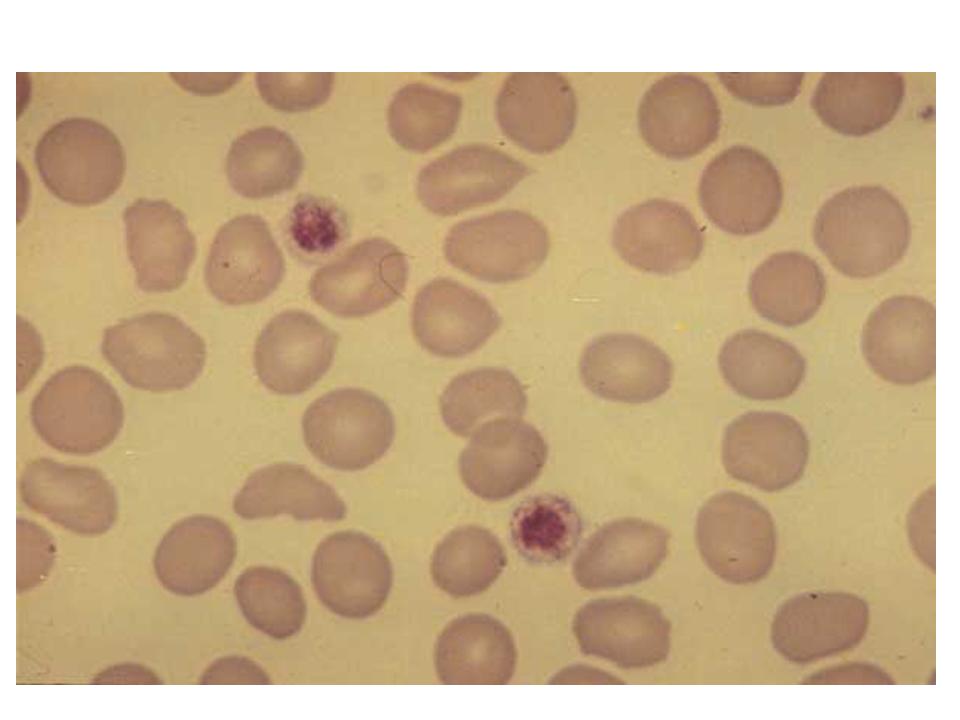

| Peripheral blood smear | Rule out pseudothrombocytopenia8Large platelets in ITP.Platelets present may look larger and younger9 than normal as bone marrow attempts to replace them quicklyHemolysis10 (in DIC, TTP, HUS) |

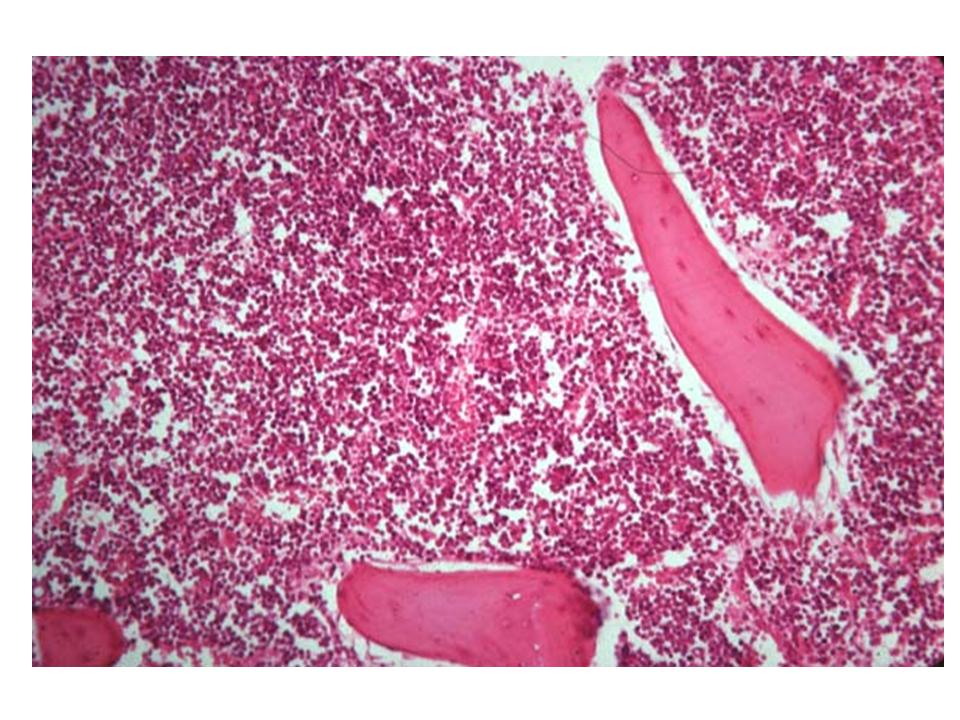

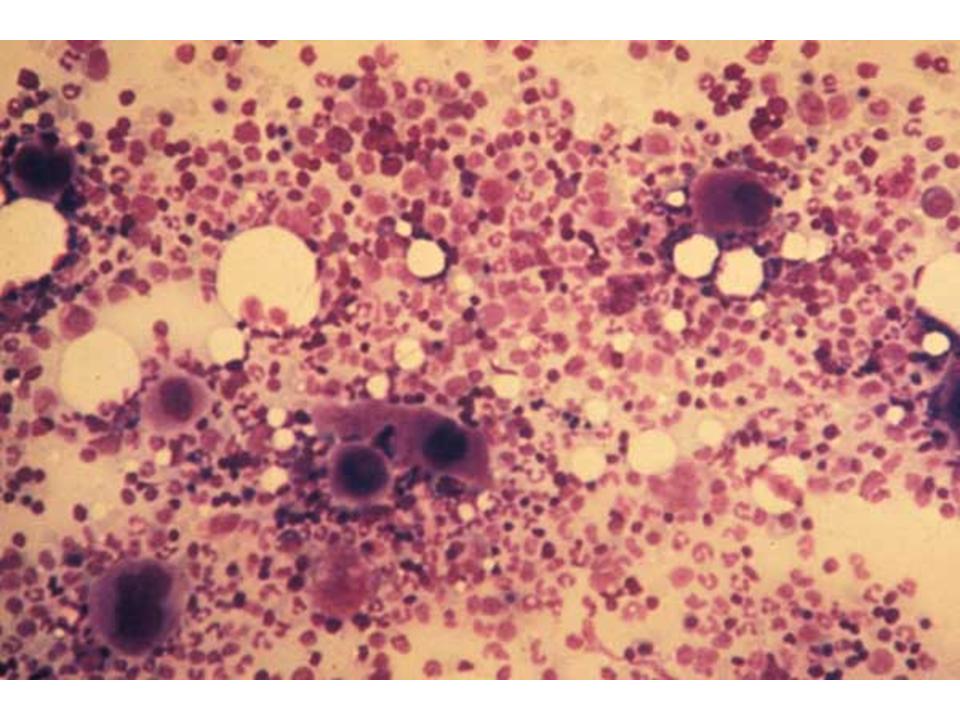

| If malignancy suspected:Bone marrow biopsy | Examine morphology of cell linesBlast cells11 suggest leukemiaMegakaryocytes12 normal or increased may help differential cause |

Hint: if the thought of a bone marrow biopsy crosses your mind, it is important to do consider doing it before the use corticosteriods, e.g. as treatment for ITP. As corticosteriods modulate the immune response, it may alter the appearance of the bone marrow.

IMAGES AND EXPLANATIONS

1. Petechiae: tiny pin-point hemorrhages in skin or mucous membranes due to not enough platelets to plug up the micro-leaks in small vessels each day

2. Purpura: hemorrhages larger than petechiae seen in the skin

3. ITP: The cause is not known for certain, but the body makes autoantibodies against its own platelets causing phagocytosis and clearance in the spleen. At least half of patients presenting with ITP have a preceding viral infection, which may have triggered the autoimmune process via molecular mimicry. ITP is the most common cause of acute thrombocytopenia in the well child.

4. NAIT: Pregnant mothers become sensitized to an antigen on their baby’s platelets (most commonly human platelet antigen 1a) and produce antibodies against them. If these antibodies cross the placenta, the fetus’s platelets will be destroyed. (See section on neonatal thrombocytopenia)

5. TTP: This is an inherited or acquired defect that causes microthrombi formation in small vessels. High molecular weight multimers of von Willebrand factor (vWF) cause platelet aggregation. The body makes an enzyme (a metalloprotease) that breaks down these vWF multimers to prevent too much clotting of platelets. In the inherited form of TTP, this enzyme is defective. In acquired TTP, a preceding infection likely triggers the body’s production of an inhibitory antibody to this enzyme.

6. Hypersplenism: Normally at any given time, the spleen contains about one-third of the body’s total platelets. In severe splenomegaly, up to 90% of total platelets can been pooled in the spleen. This is not necessarily associated with increased clearance of platelets by the spleen.

7. Platelets are not stable in blood products. If a patient requires a massive transfusion of blood that has lost much of its platelets, this blood will dilute the platelets in the patient’s own blood.

8. Pseudothrombocytopenia: an in vitro artifact where platelets have clumped after collection and the individual platelets appear low.

9. Larger platelet size on peripheral smear in ITP

10. Schistocytes (suggesting hemolysis) combined with few platelets on smear makes DIC, TTP, and HUS more likely.

11. Hypercellularity seen in the bone marrow biopsy of a patient with leukemia.

12. Number of megakaryocytes slightly increased in an otherwise normal bone marrow biopsy in ITP.

References

Buchanan GR. Thrombocytopenia during childhood: what the pediatrician needs to know. Pediatr Rev. 2005 Nov;26(11):401-9.

Chu YW, Korb J, Sakamoto KM. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Pediatr Rev. 2000 Mar;21(3):95-104.

Hoffbrand AV, Pettit JE, Moss PAH. Essential hematology. Fourth edition. Blackwell Science, 2004.

Acknowledgements

Written by: Joanne Yeung

Edited by: Anne Marie Jekyll

(31 votes, average: 4.68 out of 5)

(31 votes, average: 4.68 out of 5)