Background

Cervical palpation very often identifies one or more neck mass in the pediatric patient. The differential diagnosis is extensive, but diagnosis is made often with history and physical alone.

An understanding of surface anatomy, lymphatic drainage patterns in the neck, and head and neck embryology are extremely useful in diagnosis. Typically three primary categories of neck masses are described:

- Inflammatory

- Congenital

- Neoplastic

Other causes include traumatic, metabolic, autoimmune, and idiopathic conditions, not discussed here.

Most pediatric masses are the result of a self-limited bacterial or viral infection. It is important to be able to distinguish inflammatory masses or normal neck structures from masses that require intervention or referral.

Historical investigations

Patient age and duration of symptoms are the most important points in historical evaluation.

| Abnormal historical features: |

Demographic characteristics

|

Mass size over time

|

Head and Neck symptoms

|

Systemic symptoms or other body systems

|

Risk factors for infection or malignancy

|

Physical Examination

An accurate description of the location and palpable characteristics of the mass or masses is the most important aspect of the physical exam. A full Head and Neck examination should also be done to identify any primary sites of malignancy or infection, including tympanic membranes, nasal mucosa, and oropharynx.

Mass characteristics indicate much about the underlying pathology (Adapted from (2))

| Characteristic | Normal | Abnormal |

| Size | <1cm | >1.5cm |

| Mobility | Mobile | ¯ or fixed |

| Consistency | Soft, fleshy | Firm, rubbery, matted |

| Parotid or thyroid gland mass | No | Yes |

| Hoarseness, stridor | No | Yes |

| Otalgia with normal ear exam | No | Yes |

| Neck muscle weakness or altered sensation | No | Yes |

- Though mass tenderness is important to note and may be indicative of inflammation, it may not be especially useful as infectious, congenital, and neoplastic masses can all be tender or nontender at different times.

- Otitis media is common in children so unilateral serous effusion is less worrisome than in adults, particularly if there is was diagnosis of acute otitis media in recent weeks (or chronic/recurrent otitis media)

- Supraclavicular or posterior triangle masses are more suspicious than anterior chain adenitis

Differential Diagnosis

Many neck masses tend to occur in consistent locations:

| Midline | Thyroglossal duct cyst, ectopic thyroid tissue, dermoid, teratoma |

| Associated with sternocleidomastoid (SCM) | Branchial cleft anomalies |

| Associated with thyroid gland | Diffuse enlargement or nodule of thyroid (benign or neoplastic) |

| Associated with major salivary glands | Sialoadenitis, salivary neoplasm |

| Lymph node routes clusters | Inflammatory/neoplastic adenopathy |

Malignancy

Malignant masses are uncommon in children, but when do occur are most often lymphomas or soft-tissue sarcomas. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft tissue malignancy. In contrast, in adults over 40 years of age, a malignant neoplasm causes 80% of solitary neck masses.(2)

Click here to see lymph nodes associated with metastasis

Selected congenital masses

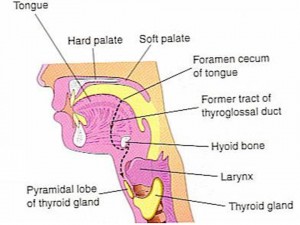

- The thyroglossal duct cyst is usually found close to midline superior to the thyroid gland and may elevate on swallowing or tongue protrusion. It is a thyroid tissue remnant left during embryological descent of the thyroid anlage from the foramen cecum of the tongue to its final position anterior to the trachea. Removal by a head and neck surgeon is often recommended due to risk of future inflammation/infection.

Fig. 2: Path of descent and sites of ectopic thyroid remnants during embryonic development. (From (4))

- Branchial cleft cysts will often present as a mass under the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A sinus/fistula tract opening may be visible on the skin anterior to the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and it may enlarge rapidly after an URTI. Saliva or mucoid/mucopurulent material may be seen to drain from it and there may be communication with the aerodigestive tract. Several variants exist. Branchial cleft cysts, sinuses, and fistulae are remnants of pharyngeal embryological development, description of which being too complex for this discussion. Careful note should be made of external ear malformations or pits, facial nerve palsies, and hearing deficits. If suspected, referral to an otolaryngologist should be made for assessment and possible excision.

- Hemangiomas are the most common of all congenital anomalies. They often present as a soft, painless, and compressible mass on any skin or mucosal surface or within bone, muscle, or glands. Hemangiomas near the skin are usually red to violaceous. Many different types exist, from a port wine stain, for example, which is a pink or red mark that does not blanch with pressure, to a cavernous hemangioma, which is a red or purple “bag of worms” that increases in size on valsalva. They result from inappropriate development of vascular endothelium and channels and associated nervous components. Spontaneous involution is most common. Observation is initally recommended, but referral may be made to a dermatologist, plastic surgeon, or head and neck surgeon, as required for persistent lesions.

- Lymphangioma or cystic hygromas are uncommon benign cystic masses that are soft, slow growing, painless masses with a doughy consistency. Often they can be transilluminated. They rarely present at birth but develop during the first several months of infancy. Most present before 2 years of age. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice but recurrence rates are high.

Summary

Most often, pediatric neck masses are inflammatory cervical lymphadenitis that can be observed for 2 weeks with or without antibiotic therapy dependent on suspected etiology. However, there should be a strong index of suspicion for potentially malignant masses and immediate referral should be made to a head and neck surgeon for further evaluation.

REFERENCES

(1) Eric Schwetschenau, Daniel J Kelly. The Adult Neck Mass. American Family Physician 66[5], 831-838. 2002.

Ref Type: Journal (Full)

(2) William B Armstrong, Mark F Giglio. Is this lump in the neck anything to worry about? How to recognize warning signs of an abnormal mass. Postgraduate Medicine 104[3], 63-76. 1998.

Ref Type: Journal (Full)

(3) Kyle Kennedy, Norman Friedman. Pediatric Head and Neck Tumors. Francis Quinn Jr, editor. Grand Rounds Presentation, Department of Otolaryngology, University of Texas Medical Branch . 1999.

Ref Type: Report

(4) Keith L Moore, T.V.N.Persaud. The Pharyngeal (Branchial) Apparatus. In: Keith L Moore, T.V.N.Persaud, editors. Before We Are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: W.B. Saunders Company, 2005: 197-239.

Acknowledgments

Written by: Stephen Kennedy

Edited by Jeff Bishop

(20 votes, average: 3.95 out of 5)

(20 votes, average: 3.95 out of 5)