Background

Definition: Constipation is defined as a delay or difficulty in evacuating stool. The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition define constipation as “a delay or difficulty in passage of bowel movements present for two or more weeks, which causes the patient significant distress”. The definition of constipation becomes confusing at times because parents may have very different interpretations of constipation. In addition, the frequency and types of stools change with growth and development and thus the definition must be adjusted accordingly:

- First week of life – 4 stools per day (though this may be far less if the infant is breast-fed)

- Second week to 3 months – 3 stools per day if breast-fed; 2 stools per day if formula-fed

- 2 years old – slightly less than 2 stools per day

- > 4 years old – slightly greater than 1 stool per day

General Presentation

Constipation is common in children. Children have an increased tendency to constipation during 3 stages of their lives:

- Introduction of cereals and solid foods

- Toilet training

- The start of school

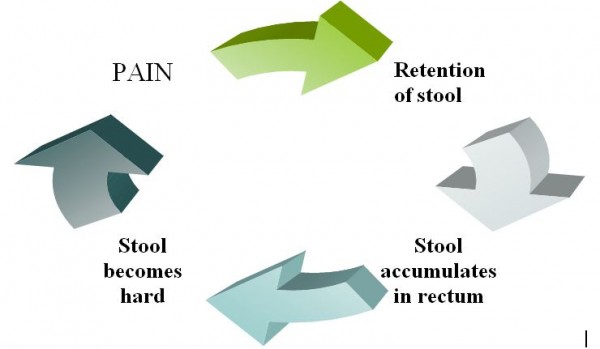

These stages represent defecation challenges to the child and the possibility of an unpleasant and frightening experience, which in turn may lead to the conscious or unconscious avoidance of defecating. This is described as functional constipation and becomes a cycle. If defecation is associated with pain, the child avoids having a bowel movement and the stool accumulates in the rectum and becomes even harder. Now the process of defecation becomes even more painful and the child avoids having a bowel movement even more that he/she did before. This cycle is known as the pain retention cycle and will not end until the bowel movements are no longer painful.

Figure 1: The Pain Retention Cycle

The child may present with infrequent bowel movements, hard, pellet-like stools, large stools with painful defecation, anal fissures and and/or encopresis (soiling of the underwear). Soiling occurs as a result of overflow of excessive fecal contents due to the child retaining stool and dilating the rectal wall. A child that is voluntarily withholding their stool may also present with “retentive posturing”; that is standing or sitting with their legs straight and stiff or crossed legs. A child may also hide in a corner and/or become red in the face from straining to hold stool in.

The Rome II Guidelines categorizes functional gastrointestinal problems in children into four broad categories.

- Infant dyschezia – In an otherwise healthy infant under 6 months of age, prolonged straining and crying (at least 10 minutes) prior to having a soft bowel movement.

- Functional constipation in infants and preschool children – At least 2 weeks of pebble-like hard stools two or fewer times per week without evidence of an organic cause.

- Functional fecal retention – At least 12 weeks of passing large stools less than twice a week and where the child avoids having a bowel movement by consciously contracting the pelvic floor muscles, presenting as retentive posturing. These children thus often present with abdominal cramping, encopresis and loss of appetite.

- Functional non-retentive fecal soiling – Inappropriate defecation in the absence of fecal retention or organic disease. Be aware that school-age children soiling themselves or having bowel movements in unacceptable places may have emotional disturbances.

Questions to Ask

Good history taking is crucial. The most important aspect of a constipation history is to determine whether it is functional or organic constipation. Organic constipation accounts for less than 5% of children with constipation. Pay specific attention to environmental factors surrounding the child’s constipation such as the start of toilet training or attending school.

Parents often come to the physician with the concern that their child is constipated because they are straining and their face is turning red when they have a bowel movement. It is important to note that apparent straining does not necessarily indicate constipation; infants are at mechanical disadvantage as they are supine while defecating and have weak abdominal muscles.

The first bowel movement in a full term infant should occur in the first 36 hours of life. Remember to ask about neonatal constipation.

It is a good idea to ask parents to bring in a dietary and symptom diary of the past week. Ensure parents are recording stool frequency, appearance, consistency, and any associated pain. Functional constipation is typically diagnosed based on history although they often have stool retention on physical exam. Features that raise suspicion of an organic cause of constipation include the following: Delayed growth, failure to thrive, urinary incontinence/bladder disease, constipation from birth or onset before 1 year of age, delayed passage of meconium, acute constipation, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, passage of blood, absence of withholding or soiling, extraintestinal symptoms and/or failure to respond to conventional treatments. Any of these features requires a more thorough work-up to rule out organic causes. A family history of chronic constipation is also important to elicit.

Finally a dietary history is critical in determining the underlying cause of a child’s constipation. Children consuming a diet high in processed foods and lack of fiber are more likely to experience constipation.

Differential Diagnosis of Constipation

- Functional constipation: These children have no lab abnormalities suggestive of an organic etiology. The history essentially makes this diagnosis. Functional constipation is associated with infrequent, difficult and often incomplete defecation. The child may have a dilated rectal vault, soiled underwear, fecal impaction and palpable fecal mass in the left lower quadrant. Otherwise the physical exam is normal.

- Dietary: Lack of fiber and increased consumption of processed foods.

- Hirschsprung disease: A disease caused by the failure of ganglion cells to migrate into the distal bowel resulting in the affected segment of colon failing to relax and causing a functional obstruction. This disease is characterized by a failure to pass meconium within the first 24 hours of life, abdominal distension, an empty rectum, vomiting and occasional fever. Dilated loops of bowel may be seen on abdominal x-ray proximal to the aganglionic segment.

- Anorectal and colonic malformations: Constipation from birth, often easily diagnosed with physical exam. Barium enema confirms the diagnosis. Examples include anal stenosis, anteriorly displaced anus, imperforate anus, and colonic strictures.

- Multisystem disease: Presents with disease-specific symptoms.

- Cystic fibrosis (CF): Autosomal recessive disease as a result of a mutation in a chloride transporter gene. Meconium ileus is pathognomic of CF. Presenting symptoms include failure to thrive, recurrent pulmonary infections, pancreatic insufficiency and elevated sweat chloride levels.

- Hypothyroidism: Symptoms include constipation, lethargy, macroglossia, cold intolerance, dry skin, brittle hair prolonged jaundice, short stature and facial puffiness. A thyroid goiter may sometimes be palpable.

- Celiac disease: Gluten allergy that occasionally presents with constipation likely because of reduced food intake.

- Developmental delay: These children have a diminished capacity to become toilet trained and may have a decreased ability to perceive the need to have a bowel movement.

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 (MEN2): Constipation may be the first presenting sign of MEN2 syndrome. Other symptoms include abdominal distension, abdominal pain, difficulty swallowing and vomiting.

- Muscular dystrophy

- Diabetes mellitus

- Spinal cord abnormalities: There is a history of swelling or exposed neural tissue in the lower back and incontinence. On exam, there may be a visible abnormality of the lumbosacral area such as a hairy tuft and sphincter axity may be observed. MRI of the cord reveals abnormalities. Examples include meningomyelocele, tethered cord, and sacral teratoma.

- Drugs/Toxins

- Lead poisoning: Sporadic vomiting, abdominal pain and constipation at levels as low as 2.90 micromoles/L

- Infantile botulism: A neuroparalytic syndrome as a result of the botulin neurotoxin associated with honey. The presentation varies including constipation, weakness, feeding difficulties, anorexia, global hypotonia and drooling.

- Narcotics

- Psychotropics

- Cow’s milk intolerance: Associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, enterocolitis and constipation.

Procedures for Investigation

- Physical xam: Always begin with general observation of the child. Is this child well or ill? Are they failing to thrive or gaining weight appropriately. Complete an abdominal exam with careful attention paid to the perianal area looking for sensory and motor deficits, a patent anus, and an absent cremasteric reflex. Examining the sacrococcygeal area for hair tufts is also important as they are associated with spinal cord abnormalities. The digital rectal exam is also critical in children with constipation. A distended rectum, full of stool is indicative of functional constipation whereas a tight, empty rectum with failure to thrive points more towards Hirschsprungs disease.

- Fecal occult blood testing.

- Urinalysis and urine culture – this is particularly important in children with encopresis as fecal impaction mat predispose to urinary tract infection due to compression effects on the bladder by the distended rectum.

- Complete blood count (CBC) and differential – to look for anemia.

- Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thryoxine (T4) levels

- Lead level – important if the child is at risk for lead poisoning.

- Calcium and electrolyte levels

- Plain abdominal film – to visualize retained stool.

- Barium enema – useful to investigate for structural causes of constipation and Hirschsrpung’s disease (may see aganglionic segment of bowel).

- MRI of the lumbosacral spine – to look for tethered cord and tumors in children with non-resolving constipation or clinical signs of spinal abnormalities.

- Anorectal manometry – to measure the neuromuscular function of the anorectum; this investigation is important if you are suspecting Hirschsprung’s disease.

- Colonic transit studies – to distinguish disorders of motility from outlet obstruction. Children that present with intractable constipation may actually have “slow transit” constipation which results from abnormally slow transit of digested food through the colon.

Conclusion

Constipation is a very common problem among children. The majority of constipation is functional and revolves around changes occurring in the child’s life such as the transition to solid food, toilet training and starting school. Parents should be educated about functional constipation and supported to help the child break the retention cycle. It is extremely important however, to recognize organic causes of constipation and perform diagnostic tests so that appropriate therapy can be initiated.

Supplementary Information – Recommendations for Treating and Preventing Constipation

Early intervention in both acute and recurrent constipation is crucial to preventing complications such as anal fissures, encopresis and chronic constipation. As constipation characteristically arises during specific times in a child’s life, it is important that the physician provide some anticipatory guidance at regular well child visits. Such guidance includes maintaining a minimum daily fiber intake in grams equal to the child’s age in years plus 5 grams and a fluid intake ranging from 960-1920mL (32-64 ounces) per day. In addition a child should not drink more than 720mL (24 ounces) of whole cow’s milk per day.

A child who presents with painful defecation should have a course of stool softener to alleviate the fear of passing a bowel movement. This may be the only method to break the pain-retention cycle. The stool softener should be non-habit forming and palatable. Safe and effective choices include electrolyte free polyethylene glycol, mineral oil and milk of magnesia. Also, encourage the child to site on the toilet in the morning upon waking and after meals as the colon is maximally active during these times.

Finally, children who are unable to pass stool for several days may be treated with a sodium phosphate enema followed by a laxative.

References

- Ferry, GD. Constipation in children: Etiology and diagnosis. Up To Date 2007.

- Ferry, GD. Prevention and treatment of acute constipation in infants and children. Up To Date 2007.

- Kleigman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jensen HB, Behrman RE. Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics 5th Edition. Elselvier Saunders, 2006.

Acknowledgements

Written by Anne Marie Jekyll

Editted by Elmine Statham

(7 votes, average: 4.57 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 4.57 out of 5)