Click for word document: Approach to Skin Lesions

Background

Your skin is not only your largest organ but is also an integral component of the body’s defence system. Disease or impairment of the skin’s normal function can lead to significant morbidity and mortality1. In addition, the skin can serve as a window for the evaluation of internal health and disease. In fact, skin lesions may be the first clinical sign of significant systemic diseases such as meningococcemia or chicken pox. This is particularly so in pediatrics where many infectious diseases may present with cutaneous lesions. The skin is also a significant part of how we present ourselves to the world and as such carries great significance for social and psychological wellbeing.

Skin disease will undoubtedly be something you will be confronted with in your training and medical career. Community studies have shown that over 20% of the population have a medically significant skin condition,and up to 1/3 of visits to family practitioners are for dermatologic concerns1, 2. Clinical examination and recognition of skin lesions is key to diagnosis as few tests are necessary or useful1. As such, developing an approach to assessing skin lesions and having knowledge of common skin conditions will serve you extremely well throughout your career, regardless of your specialty.

Skin conditions can be broadly classified into three categories based on their cause:

1) Inflammatory

2) Infectious

3) Systemic

For a review of some common paediatric skin conditions please refer to the Common Paediatric Skin Conditions & Birthmarks module on this site.

Dermatologic Terminology

The term skin lesion refers to any cutaneous surface change. The terms used to describe dermatologic lesions are unique, specific and highly important for accurate diagnosis and communication2.

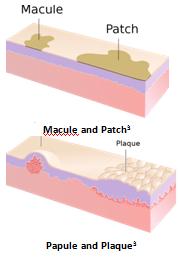

Primary Lesions: Those lesions that are the direct result of a pathologic process

- Macule: Small, flat, non-palpable lesion (<1 cm). Non-palpable. Example: Freckle

- Patch: Large, flat, non-palpable lesion (>1 cm). Example: “Cafe-au-lait” spot

- Papule: Small, elevated, palpable lesion (<1 cm). Example: Wart

- Plaque: Large, elevated, palpable lesion (>1 cm). Example: Psoriasis

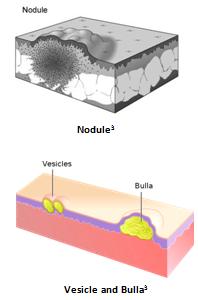

- Nodule: Small bump (<1 cm) with significant deep component (must be palpated to appreciate). Example: Enlarged lymph node

- Tumor: Large bump (>1 cm) with significant deep component (must be palpated to appreciate). It is important to distinguish this use of the word from its more common use in describing neoplasms.Example: Xanthoma

- Vesicle: Small fluid-containing lesion (<1 cm). Example: Blister

- Bulla: Large fluid-containing lesion (> 1 cm). Example: Blister

Table 1. Common Primary Lesions4

| Profile | <1 cm | >1 cm | |

| Flat | Macule | Patch | |

| Elevated | Papule | Plaque | |

| Palpable, deep | Nodule | Tumor | |

| Fluid filled | Vesicle | Bulla | |

Modified from Toronto Notes 2010

- Cyst: Sac containing semi-solid or fluid material. Example: Sebaceous cyst

- Pustule: A puss containing lesion. Variables sizes. A follicular pustule, of the hair follicle, generally indicates local infection while a Non-follicular pustule may indicate systemic infection. Example: Abscess

- Folliculitis: Superficial, usually multiple

- Furuncle: Deeper version of folliculitis

- Carbuncle (“boil”): Deep, coalescence of multiple follicles

The following primary lesions have such a characteristic morphology that they have specific names:

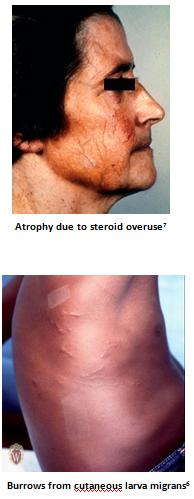

- Atrophy: Thinning of epidermis and/or dermis.

- Burrow: Small threadlike curvilinear papule produced by skin infestation. Virtually pathognomonic for scabies.

- Comedone: Plugged hair follicle. Typical of acne, they can be open (blackhead) or closed (whitehead).

- Fibrosis / Sclerosis: Scarring/thickening of the dermis.

- Hypertrophic scar / Keloid: Hypertrophic scars and keloids are characterized by the growth of excess scar tissue. The distinction is that hypertrophic scars do not overgrow the original wound boundaries, whereas keloids do.

- Milium: Small superficial cyst containing keratin, typically 1-2mm in size.

- Petechiae / Purpura: (1-2 mm & 3-10 mm respectively) Like tiny bruises, these are red or purple macules caused by capillary hemorrhage under the skin or mucous membrane. They may be palpable but do not blanch with pressure. Example: Thrombocytopenic purpura

- Ecchymosis / Bruise: Large (>1 cm) skin discolouration due to the presence of blood in the subcutaneous tissue resulting from ruptured vessels.

- Telangiectasia: A dilation of superficial dermal vessels visible on the skin or mucous membranes. Example: Spider angioma

- Wheals / Hives: Transient (<24 hours) well-circumscribed, superficial edematous papules or plaques. They may be white to pale red and often appear and disappear over a period of hours. Example: Urticaria

Secondary Lesions: Lesions that are the result of alteration or evolution of a primary lesion (e.g. rubbing, scratching, infection)2,4

- Crust: Dried remains of serum, blood or pus overlying involved skin. Example: Scab

- Excoriation: Traumatized or abraded skin, usually due to scratching or rubbing.

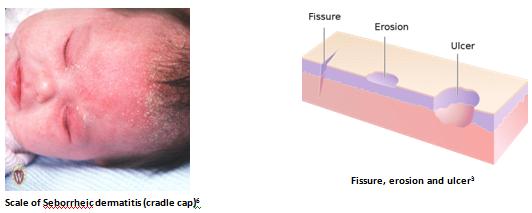

- Fissure: Linear, often painful crack in the skin.

- Lichenification: Accentuation of normal skin lines/creases due to chronic rubbing/scratching.

- Maceration: Raw, moist tissue. Typically found in body folds.

- Scale: Flakes of keratin that can be fine or coarse; loose or adherent. Example: Dandruff

- Erosion: Superficial open wound involving only epidermis or mucosa. Does not extend into the underlying dermis, so healing occurs without scar formation.

- Ulcer: Deep open wound extending into the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. May lead to scar formation. Example: Diabetic foot ulcer, Canker sore

Colours:

- Erythematous: Red

- Violacious: Purple

- Yellow: As you’d expect. Often suggests presence of lipid or jaundice.

- Pigmented: Usually used to describe brown, black or grey lesions.

- Hypopigmented: A decrease in normal brown/black colouration.

- Depigmented: Total absence of normal brown/black colouration. As in Vitiligo

- Hyperpigmented: An increase in normal brown/black colouration.

Shape/Texture:

- Polygonal: Many-sided, like a polygon.

- Targetoid: Like a bullseye. Nearly pathognomonic for erythema multiforme.

- Umbilicated: Lesion with a central dell.

- Verrucous: Rough surface texture, like that of a wart.

Arrangement:

- Solitary: Single lesion.

- Grouped: Gathered together.

- Linear: Resembling a straight line. Often suggests external cause such as poison ivy.

- Annular: Ring-like.

- Arcuate: Curved, resembling an arc(s).

- Polycyclic: Multiple curves, like the edge of a cloud.

- Reticulate/Reticular: Mottled.

- Zosteriform/dermatomal: distributed along dermatomal lines, like Shingles.

Physical Examination & Description of a skin lesion

In contrast to most other areas of medicine, when examining a skin lesion, it can be advantageous to examine the patient before taking a history. This is because, unlike many other medical problems, patients can see skin disease and thus may read into their condition and make incorrect assumptions that may influence the physician. Consequently, though valuable, a patient’s history is best taken after the physical to ensure objectivity and diagnostic accuracy10.

1) General Appearance: (well, uncomfortable, toxic)

2) Vital signs: (pulse, respiration, temperature, etc)

3) Skin exam: (entire skin should be inspected, including mucous membranes, genital/anal regions). Proper and complete description of a dermatologic lesion should include the following features2, 4, 10, 11:

Remember SCALDA to describe a lesion4

S Size/Shape/texture

C Colour

A Arrangement

L Lesion type (primary, secondary)

D Distribution (eg. Symmetrical, dermatomal, follicular, extensor surfaces, intertriginous (between body folds), dependent areas, sun-exposed skin)

A Always check condition/involvement of mucous membranes, nails, hair and intertriginous areas.

Example Lesion Description for Acquired Nevomelanocytic Nevus (Common Mole):

- Small (<1cm), round, uniformly tan, brown or black macules/papules. Scattered, discrete lesions that are well-circumscribed with smooth, regular borders.

History

A basic dermatology history should include the following2, 4, 10:

1) History of skin lesion(s)

- Onset

- Body location

- Associated symptoms: itching (pruritis) or pain

- Pattern of spread

- Any change/evolution of individual lesions

- Provocative factors: heat, cold, sun, exercise, travel, medications, pregnancy, season

- Prior treatments

2) Constitutional symptoms

- Acute: headache, chills, fever, weakness, night sweats

- Chronic: fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss

3) Medications

4) Allergies

5) Past Medical History: including atopic history (asthma, hay fever, eczema)

6) Family Medical History: especially psoriasis, atopy, melanoma, etc

7) Social history: with focus on travel or exposures

Investigations

Dermatological lesions are, by their nature, relatively easy to examine and diagnose without the need for many complex investigations. Frequently, however, biopsy may be done to confirm or establish a diagnosis1. Specific investigations are beyond the scope of this module. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended if there is concern about the severity of symptoms or prognosis.

Conclusion

Having an approach to the evaluation of skin lesions is immensely useful as dermatological conditions are so very common. Recognition of skin lesions is of particular importance in paediatrics where significant systemic diseases, such as meningococcemia, may first become apparent by recognition of characteristic skin lesions. It is also important to have a good understanding of appropriate terminology so that a clear picture of the lesion can be conveyed to colleagues2. Lastly, always remember that the skin’s function as a barrier to infection is of paramount importance and as such any break in the skin or mucous membranes must be treated appropriately to avoid infection.

References

1) Buxton, P. ABC Atlas of Dermatology, 4th Ed (2003). BMJ Publishing, London.

2) Lui, H. Gross Anatomy/Pathology of the Skin and the Language of Dermatology. UBC Medicine Lecture (2010).

3) Madhero88. Wikipedia Commons (2011). http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Madhero88. Accessed April 24, 2011.

4) Lo, V., et al. “Chapter 5. Dermatology” (Chapter). Baxter, S. & McSheffrey, G. Toronto Notes 2010 26th Ed: Dermatology chapter (2010). University of Toronto. Toronto.

5) Fruitsmaak, S. Wikipedia Commons (2010). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Inflamed_epidermal_inclusion_cyst.jpg. Accessed September 10, 2011.

6) Williams, G & Katcher, M. Primary Care Dermatology Module – Nomenclature of Skin Lesions (2003). http://www.pediatrics.wisc.edu/education/derm/index.html. Accessed April 29, 2011.

7) Bezzant, J. Dermatology Image Bank (2000). http://library.med.utah.edu/kw/derm/. Accessed September 10, 2011.

8) Silver442n. Wikipedia Commons (2007). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Milia_big.png. Accessed September 10, 2011.

9) Elecbullet. Wikipedia Commons (2009). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Blackheads.JPG. Accessed September 10, 2011.

10) Wolff, K. &, Johnson, A. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology 6th Ed (2009). Mcgraw-Hill. New York. http://www.accessmedicine.com/resourceTOC.aspx?resourceID=45

11) Yang, J., Brierley, Y., Hong, Chih-ho., Shapiro, J. & Lui, H. UBC DermWeb (2007). http://www.dermweb.com/teaching/. Accessed May 5, 2011.

All images sourced with permission

Acknowledgements

Written by: Magnus Macnab, UBC Medicine, Class of 2012

Edited by: Anne Marie Jekyll, MD (Pediatric Resident)

(21 votes, average: 4.05 out of 5)

(21 votes, average: 4.05 out of 5)