Click for pdf: Abdominal Mass

General Presentation

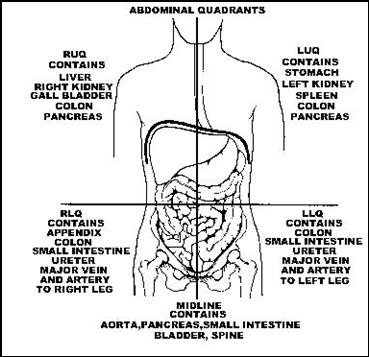

An abdominal mass in a neonate, young child, or adolescent patient is something that every pediatrician needs to be wary of as these masses can indicate malignancy. The differential for an abdominal mass can be extensive and quite daunting, as it incorporates many systems including the gastrointestinal (GI), genitourinary (GU), and endocrine system (table 1). An organized approach to abdominal masses includes thinking about possible etiologies based on the location of the mass with regards to the underlining abdominal anatomy (figure 1) as well as discerning likely pathologies based on the age of the patient and associated symptoms or signs.

General presentation varies depending on the underlying pathology of the abdominal mass. Patients can present with difficulty with urination or defecation if the mass physically obstructs the GI or GU tract. Patients presenting with constitutional symptoms such as fever and weight loss with an abdominal mass are more likely to be suffering from an malignant condition. Neuroblastoma and Wilms tumour are two conditions you must be vigilant about as they are the two malignant tumors in children where abdominal mass is commonly the initial presentation.

Neuroblastomas arising from the abdomen (the most common type) typically presents with abdominal pain. If the mass presents in the pelvic region, obstruction of the GI or GU tract can occur. Nueroblastomas can also present as paraspinal tumors and this can present back pain or paraplegia. Wilms tumors all arise from the kidney and can present as an asymptomatic abdominal mass, or can be associated with abdominal pain, hematauria, or hypertension (with renin secreting tumors).

When attempting to diagnose an abdominal mass, a proper history with a focused gastrointestinal physical exams is necessary to direct you to the proper diagnostic tests to order, or the right specialist to refer too (i.e pediatric oncologist, surgeon, gastroenterologist, nephrologists, or gynecologist).

Figure 1

http://www.raems.com/abdopelvicart.htm

Questions to Ask

- The age of the patient is very important when approaching abdominal masses in the paediatric population and should be the first question to ask. Determining the age of the patient can differentiate between likely aetiologies (children vs neonates). In general, older children are more at risk of developing malignant masses compared to neonates and young children. Of the malignant conditions, children younger than 2 are more likely to suffer from neuroblastoma and hepatoblastoma, where as older children are more susceptible to Wilms tumour, hepatocellular carcinoma, genitourinary tract tumours, and germ line tumour

- You should also ask questions pertaining to the timeline of the abdominal mass

- Length of time since the mass was found. Masses that have been around for a long time (several months to years) are more likely to be benign

- The rate of growth of the abdominal mass. Masses that grow faster are more likely to be malignant

- Ask the patient where the mass was observed. Have an idea of the anatomical structures in each section (figure 1) and relate that to possible etiologies of the abdominal mass. For example, think hepatoblastoma, Wilm’s tumor of the right kidney, neuroblastoma of the right adrenal gland, or enlarged gall bladder if mass was found in the upper right quadrant.

- Ask the patient if they observed any gastrointestinal or genitourinary obstruction. This includes decreases in bowel movements or decrease volume of urine.

- You should ask for presence of constitutional symptoms to gauge whether a malignant pathology is present. Constitutional symptoms include pallor, anorexia, weight loss, and fever. Important to know that these symptoms are not specific for any one condition in particular.

- Ask about pre-natal interventions as well as review prenatal ultrasounds (US). This is particularly important on neonates and young infants. The US can show the presence of oligohydramnios or polyhydraminis (excess amniotic fluid) which may suggest a congenital renal etiology for the abdominal mass.

- Ask about the presence or absence of watery diarrhea. A positive finding here can indicate a vasoactive intestinal peptide secreting neuroblastoma.

- Investigate for the presence of blood in the urine. A positive finding here can clue you in to a pathology that results in damage to the genitourinary tract such as Wilms tumor.

- Look for a history of cramping, abdominal pain and vomiting. Positive findings for these symptoms can point you to pathologies of the gastrointestinal tract such as intussusception of volvulus

Differential diagnosis

| Organ | Malignant Diseases | Nonmalignant Diseases |

| Adrenal | Adrenal carcinoma

Neuroblastoma Pheochromocytoma |

Adrenal Adenoma

Adrenal Hemorrhage |

| Gall bladder | Leiomyosarcoma | Choledochal cyst

Gall Bladder obstruction Hydrops (eg, leptospirosis) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Leiomyosarcoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Appendiceal abscess

Intestinal duplication Fecal Impaction Meckel’s Diverticmulum |

| Kidney | Lymphomatous nephromegaly

Renal cell carcinoma Renal Neuroblastoma Wilms tumor |

Hydronephrosis

Multicystic kidney Polycystic kidney Mesoblastic nephroma Renal Vein thrombosis Hamartoma |

| Liver | Hepatoblastoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma Embryonal sarcoma Liver metastases Mesenchymoma |

Focal nodular hyperplasia

Hepatitis Liver abscess Storage disease |

| Lower genitourinary tract | Ovarian germ cell tumor

Rhabdomyosarcoma of bladder Rhabdomysarcoma of prostate |

Bladder obstruction

Ovarian cyst Hydrocolpos |

| Spleen | Acute or chronic leukemia

Histiocytosis Hodgkin lymphoma Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Congestive Splenomegaly

Histiocytosis Mononucleosis Portal hypertension Storage disease |

| Miscellaneous | Hodgkin lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma Pelvic neuroblastoma Retroperitoneal neuroblastoma Retroperitoneal rhabdomyosarcoma Retroperitoneal germ cell tumor |

Teratoma

Abdominal hernia Pyloric stenosis Omental or Mesenteric cyst |

Physical examination

Physical exams in a very young child can be difficult. Substituting the examination table with a parent’s lap is a good way of calming the nerves of an anxious and apprehensive child. Make an effort to warm your hands prior to examination to minimize discomfort. Distraction by the physician or parents can aid in the examination by relaxing the abdomen of a nervous child

A complete general physical exam with vitals (including BP!)

- Measure height and weight and plot findings on a growth chart.

- Inspection: Done with the patient supine. Look for evidence of protrusion, bulging, or asymmetry on the abdomen.

- Auscultation: Listen for bowel sounds to assess for intestinal obstruction

- Palpation: light palpation of 4 quadrants and flank area. Followed by deeper palpation of the after mentioned quadrants. palpate mass for tenderness, and texture. Look for guarding.

- Percussion: Useful for determining organ size, such as the liver. Useful for determining if the mass is a fluid filled cyst with dull percussion or an air-filled structure which will sound tympanic upon percussion. This is another opportunity to look for guarding.

- Examine the eye and the area around the eye. Bruising around the eye (periorbital ecchymosis) and bulging eyeballs (proptosis) may indicate metastatic neuroblastoma. Patients that lack an iris (aniridia) with abdominal masses most likely have a Wilms tumor.

- Take the temperature of your patient. A fever may indicate an infection. Hepatitis, mononucleosis, or leptospirosis are three infections that can cause abdominal masses derived from the liver, the spleen, and the gallbladder respectively

Radiologic Imaging

- Plain abdominal x-ray: This would be the first imaging study that you will order. This test helps you determine the location and density of the abdominal mass. Plain abdominal radiograph can be useful for detecting obstruction by looking for the presence of multiple air fluid levels or absence of air in the rectum. Calcification seen using this modality may indicate the presence neuroblastoma, teratomas, kidney stones, or biliary stones.

- Ultrasound: Inexpensive and safe modality used to complement the abdominal X-ray. Useful for discerning between solid versus cystic mass

- Computed tomography (CT) scan: Used to attain more specific anatomic information of the abdominal mass. When you’re dealing with a malignant lesion, a CT scan can be used to determine invasion of the malignant lesion to adjacent structures.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Again, like CT, used for greater anatomic detail. Is warranted in situations where the brain and spine needs to be imaged with patients presenting with neurologic deficits

Laboratory Studies

- Complete blood count with differential can be performed. Anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia can indicate bone marrow infiltration.

- Bone marrow biopsy and/or aspiration is indicated if one or more bone marrow cell lines are compromised

- Chemistry panel, including electrolytes, uric acid, and lactate dehydrogenase levels. An elevated uric acid or lactate dehydrogenase can suggest that a malignancy may be present. Electrolyte abnormality indicates pathology with the kidney or tumor lysis syndrome.

- Urinalysis: Hematuria or proteinuria suggests renal involvement.

- Test homovanillic acid and vanillylmandelic when you suspect neuroblastoma or pheochromocytoma respectively

- Serum B chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-feto protein can be used to find teratomas, liver, and germ cell tumours

References

- Riad M. Rahhal, Ahmad Charaf Eddine, Warren P Bishop. A Child with an Abdominal Mass. Pediatric Rounds (2006) 37– 42

- Armand E. Brodeur and Garrett M. Brodeur. Abdominal Masses in Children: Neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, and Other, Pediatr. Rev. 1991;12;196-206

- RAEMS: Abdominal/Pelvic Emergencies [Online]. Sited [2007], Available from: http://www.raems.com/abdopelvicart.htm. (note figure was taken from this site).

Acknowledgements

Written by: Thomas Hong

Edited by: Dianna Louie

(39 votes, average: 4.18 out of 5, rated)

(39 votes, average: 4.18 out of 5, rated)